Hacer clic acá para la versión en español

In 1993, Ken, now my husband of 17 years, and I went to Guatemala. He was in graduate school and I was between jobs. Our plan was to study Spanish intensively for a month or so and to experience something of another culture. It was a pretty typical American’s plan — we would maybe learn a thing or two, no strings attached, have some stories to tell. Little did we know that for the last several weeks of our trip would be spent with Roberto, a teacher, union activist and government critic, and that these would be the last weeks he would spend in his homeland. Our little vacation coincided with an upending in the lives of Roberto and Yolanda. We have never forgotten, and those ties to them have held fast.

We went to a language school in Quetzaltenango, also known as Xela, which was a city west of the capital in the highlands. The school had an activist, leftist orientation and through the school we learned about the Peace Brigades. At the time, Peace Brigades was providing what it called accompaniment to people in war zones or dangerous areas. The theory was that Americans, Canadians and Europeans were protected by their passports and could, by extension, provide protection to people who were threatened or in danger. Or could bear witness if harm should come to political activists. We volunteered, along with many other foreigners, to sit in the hospital outside the room of a Guatemalan union activist who had been pulled from a bus along the Pan-American highway, shot in the stomach for his work filming Guatemalans in the countryside. Such were our passive acts of support.

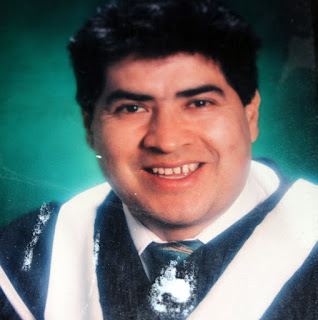

We met Roberto through one of the teachers at the language school. Like many of the Guatemalan teachers, she was moonlighting; her regular job was as the principal of an elementary school for girls. Roberto was a teacher there, one of the best, she told us, and also a member of the UTQ, the workers’ union in Quetzaltenango, which made him automatically suspect in the eyes of the government. Roberto, she told us between conjugating verbs, had been vocal in his criticism of the government. Years before, his older brother, Willy, had been a student activist. He disappeared, his body later found on a garbage heap covered with cigarette burns.

Roberto came to speak at our language school, and, being interested to see a real Guatemalan school, we visited his elementary school classroom. His students – 40 girls -- performed “Snow White and the Seven Dwarves.” Later, we listened to him give a speech during the Huelga de Dolores, a public rally held during the Easter week in which masked protesters were temporarily tolerated. Shortly after the huelga, we ran into our language teacher in town. She looked distraught, and after greeting us with kisses, pulled us aside. “Roberto came over to my house last night in a complete panic. They said if he wasn’t out of the country in a month, they would kill him.” We heard many such stories, and almost every family had a one — someone dragged away in a narrow street, snatched from a bus in a dark countryside. Sometimes there was a body to claim but most of the time, nothing.

“Is he going to leave the country?” we asked. “He must,” she replied emphatically. “He doesn’t have a choice.” We offered to help, and met Roberto in a park. Sitting on a bench, he told us what had happened. He was walking home after taking a night class. It was quiet on his street, and he could hear the crunch of the sand and gravel under his feet. A few blocks from his house, he saw two figures. They drew up to him and indicated guns under their jackets. They accused him of trying to destabilize the government, and told him he had until April 22 to leave the country. It was already mid-April. His brother had received similar threats. He worried about his mother, who had been devastated by Willy’s murder. For his own safety, and for that of his wife, Yolanda, and their two small children, Flor de Maria and Daniel, he had decided to leave the country. That was the beginning of our brief chapter in Roberto’s Odyssey.

Roberto had asked for accompaniment from Peace Brigades, but the local group had too many requests for help. So, for the next several weeks, Ken and I took on that role, simply hanging out with Roberto. It started out as a small commitment – a day or two until he was settled; I don’t honestly remember now how each day bled into the next. Things were complicated. He needed documents, an invitation from Canadians to come to their country. There were discussions with his union colleagues, plans and promises and changes of strategy. Our rudimentary Spanish and ignorance of Guatemalan bureaucracies left us ill-equipped to understand. What was clear, however, was the extent of his worry, the absolute certainty that the threats would lead to action.

Over the weeks, we stayed by Roberto’s side. It seemed unsafe to stay at his house; he lived with his wife and children at Yolanda’s parents’ home. His sister-in-law, who cared for the children while Yolanda, a doctor, was at the hospital, lived there, too. So we moved around. We bunked some nights at the UTQ headquarters on straw mattresses. One night we heard a honking horn and what sounded like gunshots outside. It was April 22 – the day Roberto was told to leave the country – and could have been a warning. No longer feeling at ease there, we moved to the grounds of the high school where Roberto’s father was the headmaster. There was a small cinderblock house where we stayed. His brothers and sisters would come by to talk, cook, and try to lift Roberto’s spirits.

We traveled with Roberto to Guatemala City to obtain documents and see what the national union could do to help. One of Roberto’s friends had given us a ride to the capital, but we took a bus home. I sat next to Roberto at the front of the bus, near the driver, and Ken sat in the seat behind us. Roberto seemed to relax, and we had a long conversation about his work and the country and his beliefs. We were traveling at night, and a few miles short of Xela the bus came to a stop at some sort of checkpoint. My heart was pounding wildly as a soldier with a gun boarded the bus. Bad things always seemed to happen on lonely roads at night in Guatemala. The soldier turned to me first and asked for my passport. I fumbled with my money belt to remove the passport, as Ken passed Roberto his sack, which he had been holding for him. The soldier glared at Roberto, but proceeded to ask people behind us for their papers. We barely breathed until the soldier had left and the bus started moving again. It was a message. If we hadn’t been there with him, he told us, he would have been dead.

One afternoon, we went with Roberto to the University of San Carlos where he was scheduled to take an exam. His brother, Willy, had been a student on campus, and a mural depicting his face was painted prominently on the side of a building there. The exam was scheduled for 6 p.m., but not long into it, the power failed and the lights went out. The proctor excused the students from the exam. But before the other students left, Roberto told them about the threats and his plan to leave the country. A number of students rose to speak, praising Roberto for his courage. One woman was crying. “Look what happens to men like you, those who aren’t afraid to speak out for justice,” she said. “You’re forced to leave the country, and we’re left here, afraid.”

Roberto eventually got to a safe house in Guatemala City. I had a flight back to the U.S., and Ken was scheduled to go to Costa Rica for a summer study program. We consoled ourselves that he was now in a safe house, that the invitations to Canada were coming, that a Peace Brigade volunteer had been assigned to stay with him. But we knew what was what: we were leaving him. We had our passports. We could get on a plane. He was still stuck in fear and limbo, and, in fact, he and Yolanda and their children faced a good deal more grueling events before finally getting to Canada.

We rejoiced when Roberto, Yolanda and their children made it to safety. And we have been so lucky to know them all these years. Roberto never stopped working for what he believed, and we’ve been awed by all the students he has taught, all the houses he’s built in Guatemala and coffee farmers he has given new hope. When we see him, Roberto always thanks us for those weeks we spent with him in Guatemala. But we didn’t do anything. We just enjoyed the company of a brave, committed, warm-hearted man. Shortly after I returned to the states, I tried to record what had happened. Recently I re-read these jottins, and was struck by this account of visiting the neighborhood where Roberto grew up. “Roberto spends the first few minutes shaking hands and greeting friends. We have grown accustomed to this. Roberto seems to know everyone. He can’t walk down any street in Xela without stopping to chat with someone he knows from his many activities: school, the various unions to which he belongs, the university, the high school that his father runs. One day, when we accompanied him to the bank, he was received warmly by security guards and tellers alike. When he left, he shook every single tellers’ hand saying, “Gracias, gracias, mucho gusto.” And I say to Roberto, we are the ones who thank you.